A talented Harvard team, full of potential, against a gritty, veteran Princeton unit with the league's best two-way player (Kareem Maddox, then, and Ian Hummer now) in a showdown for another Ivy title. The Crimson appeared to be the slight favorites in that hypothetical horse race, boasting a much stronger reservoir of young talent to fill out its rotation than the Tigers had accumulated over the past couple years.

Then, this happened.

Harvard lost its best player (Kyle Casey) and its most important player (Brandyn Curry) in one 24-hour news cycle, which when combined with the graduation losses of Keith Wright and Oliver McNally left the Crimson down four starters from last year's NCAA tournament squad. Oh, and throw in rotation guard Corbin Miller, who left the team to fulfill his two-year religious mission obligation. Those five players accounted for 62 percent of last year's total offensive possessions and included three of Harvard's four best defenders by Adjusted Plus-Minus. Most importantly, that list also included the only three Crimson players to see any time at point guard last season (Curry, McNally, Miller).

Ivy League teams just can't recover from such a talent drain, which would apply if Harvard were an ordinary Ivy team. But this Crimson team has been rather loudly stockpiling quality prospects like no other squad over the past 15 years.

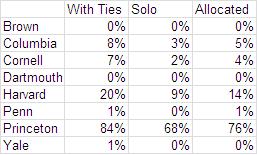

From 1997 to 2008, 37 freshman were able to crack the rotation and post an offensive rating of over 100 (national average, and above average for an Ivy player). Penn led the charge with eight such players (22% of total). Cornell followed with seven (19%), and Princeton was third with five (14%).

Now, fast forward to the Amaker era. Over the past four years, there have been 15 freshman to meet the qualifications above. Brown, Columbia, Cornell, Dartmouth, Penn and Yale have each had one. Princeton had two. Harvard has had the other seven (47%).

This superficial view obviously glosses over a number of factors, but the magnitudes are important. The Crimson has managed to bring in almost as much talent in four years as the Quakers did in 12 and almost as much talent as the rest of the league has as a whole. Even if we include the players that are clearly wrongly excluded by this analysis (Brown's Tucker Halpern and Sean McGonagill, Cornell's Shonn Miller, Harvard's Keith Wright, Princeton's Doug Davis and Ian Hummer, Penn's Zack Rosen and Miles Cartwright and Yale's Jeremiah Kreisberg - all of whom either were very close or missed due to an insane usage rate for a freshman), the Crimson would still have eight of the 24 talented rookies (33%) and the nearest competitor would have four.

This isn't the first time the league has experienced an insane talent gap for incoming players. In the early 2000s, Penn coach Fran Dunphy dominated the relatively shallow pool that defines the Ivy recruiting landscape. He nabbed six freshmen in five years who posted offensive ratings over 100 as rookies, while no other team mustered more than three.

His 2002-2003 squad remains one of the 10 best of the AI era and torched through the Ivy League en route to an 11 seed. But after the disappointing first round loss to Oklahoma State, Dunphy had to face a startling reality - only 36 percent of his team's possessions were returning next season.

The average Pythagorean Win Percentage drop for a team returning fewer than 40 percent of its possessions has been 0.272. The 2003-2004 Penn team fell just 0.072 points and remained the best team in the league by Pythag (though the Quakers did lose the Ivy race to Princeton, possibly a manifestation of the common theories about experience).

If that comp is heartwarming to Crimson fans, a more recent one won't be. The only other Top 10 Ivy team of the AI era to return fewer than 60 percent of its possessions was 2010-11 Cornell, and that Big Red squad tumbled 0.426 Pythag points finishing way back in the league race. Unlike the 2003-2004 Penn squad, however, Cornell lagged far behind its Ivy brethren in the recruiting race over the years immediately preceding the mass graduation departures.

While the Harvard discussion is fascinating from the perspective of adding a data point to the talent versus experience argument, ultimately the question that this analysis ponders is who is likely to win the league and just how likely. And the answer to those questions are Princeton and very.

After stumbling to a 2-3 Ivy start, the Tigers were essentially written off, especially since Penn and Harvard were two and three-games clear, respectively. So, I'll forgive you for not noticing when Princeton closed 8-1 and posted the second-best Ivy Pythagorean Win Percentage (0.728) behind Harvard (0.797). With the Tigers returning an above-average percent of total possessions (73 percent) and the Quakers and Crimson down in the 30s and 40s, Princeton almost becomes the default choice. That's before considering that it has the preseason frontrunner for Ivy Player of the Year and nearly has twice the home court advantage of the next closest Ivy over the past 20 years.

Harvard and Penn weren't the only teams to suffer graduation losses or adverse postseason news that dropped them from contender status. Columbia had a remarkable 2011-12 campaign even after losing its presumed star Noruwa Agho for the year, as it managed to finish as the third best Lions team in the AI era. Agho was supposed to be back with the team for a second shot at his senior season, but despite being back on campus finishing up his degree, he decided not to return to the basketball team, a crucial blow to a squad that had the makings of a potential contender.

The past is nice, but let's take a gander at the future. First, we'll start with the basics: Ivy title odds and projected wins and losses.

If there’s one thing the model has been good at thus far, it’s

picking winners. In 2010-11, it liked a Harvard-Princeton tie, with the Tigers

as slight favorites in a playoff. In 2011-12, it heavily favored a stacked

Crimson squad, which it had sitting on the cusp of the Top 50 nationally

(Harvard finished 44th).

This year, the scales have swung back toward Princeton,

which the model prefers in a rout – though not quite as strongly as last year’s

Crimson team. A decimated Harvard squad still has a fair chance of cobbling

together a three-peat and its second-straight NCAA berth, but that’s pretty

weak consolation for a team that was the betting favorite just a couple months

back.

Don’t count out Columbia and Cornell, either. As happened

last year with Penn, in a 14-game season, aligning a few positive bounces at

key moments can be the difference between finishing a few games back and having

a shot at the title in the season’s final game. If Princeton stumbles in a few league

games and makes 10-4 or 11-3 the record to beat, it’s very possible that one of

the Lions or Big Red could match that mark.

Please note that the Overall W-L only includes scheduled games and does not project yet to be determined matchups in "multi-team events." Another caveat is that all of the figures have been rounded, which leads to some minor issues. For one, Princeton is projected to finish 2.2 wins ahead of Harvard and just 3.1 wins ahead of Columbia.

The model projects Dartmouth to finish last, a place it has occupied every year since Alex Barnett went crazy on the league in 2009.

Along with the average, it's important to look at the projected variance of Ivy wins to get a sense of the probable range one can expect for any team.

Much like last year, while no individual team other than Princeton is projected to post double-digit Ivy wins, it's very likely that at least one from the group of Columbia, Cornell and Harvard will. Dartmouth is the only team at a remote risk of losing every league game, and the Tigers have an outside shot at posting the first 14-0 campaign since 2007-2008 Cornell.

While the Lions, Big Red and Crimson seem to have the inside track to the remaining upper division spots, the variance analysis makes it clear that it should be no great surprise if Penn or Yale sneaks in there, as both are 15 to 20 percent to finish with eight or more league wins.

The final thing to note is the general width of the spreads. With just 14 games, a lot of craziness can happen. Columbia's projection based on its actual Ivy performance last year was 6.2-7.8, but it went 2-7 in games decided by five points or less or in overtime and wound up finishing 4-10. Penn went 5-0 in the same type of games and turned a 9.4-4.6 expectation into an 11-3 mark. That's why almost every Ivy team is at least 10% to finish at five different win totals - a string of bad bounces in a short 14-game format can knock a team far off its true W-L expectation.

For those who inhabit the tempo-free world, here are the Pomeroy numbers for each team and the implied Pomeroy rank (based on a generic distribution of teams). The Ivy League has had at least one team finish in the Top 100 during each of the last three seasons and five teams total during that span. That stretch followed up three years of no Ivy cracking the Top 100.

Princeton is the league's best hope for extending the streak, but a lot rests on it bouncing back defensively. After boasting the 36th stingiest defense in the nation during Ian Hummer's freshman season, the Tigers have slid back over the past couple seasons, all the way back to 121st last year. That's not a huge concern if the Ivy's best offense in league play last season keeps humming along, but serious questions loom after graduating 120 three-pointers converted at over a 40 percent clip. Princeton still has plenty of offensive weapons, but it just won't be as equipped to win 95-86 shootouts like it did over Evansville in the CBI last season.

Overall, the league's defense was very good last season, with five teams ranking above average nationally. That trend should continue this year, as many of the league's teams have gotten more athletic, bigger or both. In league play last season, Ivy teams corralled 73 percent of the defensive boards, which was the second-highest rate of any Division I conference. Harvard, Columbia, Dartmouth and Yale all finished in the Top 50 nationally in defensive rebounding, generating tons of stops that can quickly drop an opposing team's points per possession.

The offense is quite a different story. Of the 14 players to use at least 20 percent of their teams' possessions and post an offensive rating of over 100 during the last campaign, just four will be playing this season. That doesn't even include various glue guys like Oliver McNally, Rob Belcore, Drew Ferry and Patrick Saunders - all of whom didn't hit the possession usage target. Top-to-bottom, the league is as well positioned to replace the lost talent as it ever has been during the AI era, but with so many key players to replace, it will still take time for the skilled newcomers to get adjusted to playing significant minutes at the Division I level.

Brown - With Tucker Halpern returning to a squad which was also adding two key frontcourt newcomers, the Bears looked poised to make a huge jump in the Ivy pecking order. Then, Brown lost Andrew McCarthy and Dockery Walker - two of its three most experience post players - in short order this offseason, severely damaging the Bears' interior depth. Now, Rafael Maia and Cedric Kuakumensah must provide quality minutes alongside Tyler Ponticelli for Brown to take a step forward in Ivy play.

The starting guard play will be solid, but not spectacular, while the backcourt depth will be quite the opposite. The Bears can win some games if they play slow and get hot from behind the perimeter, but if they get lured into track meets, the lack of depth will bury their chances.

Columbia - It was about to be the Lions' year. Well, to contend, at least. With Noruwa Agho's puzzling decision not to return for his senior season, though, Columbia lost a crucial piece at guard - a position where it already lacks serious depth. The Lions do have two quality All-Ivy pieces in Brian Barbour and Mark Cisco, as well as promising young guard Meiko Lyles and forward Alex Rosenberg.

Beyond that, though, there's just potential. But lots and lots of potential.

Sophomores Steve Frankoski and Noah Springwater and junior Van Green are the key pieces in providing the backcourt depth necessary to contend. At the very least, some strong output from those three could have the Lions looking at their first postseason appearance since 1968.

Cornell - The slow rebuilding process should take another step forward this year. Errick Peck returns to the lineup after missing a year with injury, joining sophomore Shonn Miller to give the Big Red an embarrassment of riches at the combo forward spot. Combined with some serviceable and intriguing big men, Cornell has cobbled together a pretty solid group at the 3-4-5.

The guard spots are a complete mess, however. Chris Wroblewski and Drew Ferry, who combined for 126 and 132 threes in consecutive seasons, each graduated leaving the Big Red with a hodge podge of shooting guards who can't shoot and ball handlers with no handle. Cornell has been bringing in guards by the bushel over the last couple seasons, so there should be plenty of options from which to choose in order to find a solution. If the Big Red can find two good ones, it might hang around in the Ivy race longer than most would expect.

Dartmouth - A couple years ago, the Big Green staged a coup shortly before the Ivy opener, deposing its then-coach Terry Dunn and officially hitting rock bottom as a program. Dartmouth sank to 340th in the Pomeroy Rankings, beating out just seven Division I teams (a few of them programs transitioning to the higher level).

The Big Green went back to the well, hiring Paul Cormier for a second go-around in Hanover. Cormier got to work immediately, focusing exclusively on bringing in many, many players who could potentially have Division I talent. Last season, his first full recruiting cycle, he brought in six guys and found three that could produce above replacement level. This year, he brought in seven more with as many as four looking like potential positive VORP guys in this league.

There will come a time when Dartmouth will think about filling spots or improving at certain positions, but for now, Cormier is doing the right thing. He's indiscriminately throwing talent at the problem. And that just might be enough to get his squad out of the Ivy cellar this season.

Harvard - Five freshmen. Five sophomores. Five juniors and seniors combined.

Those five juniors and seniors played a combined 40 minutes per game last year, while the five sophomores joined together to log 34. Yet despite all of the losses, there's still an incredibly interesting core to work with here.

Laurent Rivard and Christian Webster have each posted two years of three-point shooting percentages above 38. Wesley Saunders, who found himself among Rivals' Top 100 recruits coming out of high school, led the Crimson in scoring in Italy, while Kyle Casey and Brandyn Curry were still with the program. Steve Moundou-Missi ranked top five in the Ivy League in Adjusted Defensive Plus-Minus last year.

While those individual highlights are impressive, the sum total is not a team (even aside from the fact that only four players were mentioned). Harvard will have to rely on true freshman Siyani Chambers at the point. It will likely need starter's minutes from talented, but raw, Kenyatta Smith. Finally, it will need a few freshman to provide meaningful depth, since all of the quality rotation players the Crimson had expected to employ will now be starting. That's a lot of pieces to fall into place. Maybe the talent can smooth over some of the rough edges, but to fill all the gaps is probably asking too much.

Penn - There are many ways to express the enormity of what Zack Rosen accomplished last year, but here's is my favorite, by far:

Rosen used one out of every four Penn possessions last year and producing 1.13 points per. The other 75 percent of the Quakers' possessions resulted in an average output of just 0.99 points. Merely replacing Rosen's possessions with that average would have cost Penn roughly 30 Pomeroy Ranking spots. So, it should be of no surprise that Rosen's 2012 campaign was the fourth-best offensive showing of any Ivy player since 1997.

Add to the list of necessary replacements Tyler Bernardini and Rob Belcore, and its easy to see why few pundits have the Quakers cracking the Ivy's upper division, much less repeating as first runner-up. It's Miles Cartwright's turn to be the man now, and an above average frontcourt will be there to support him defensively. Whether or not Penn can be competitive at all, though, comes down to the development of its promising freshman guards.

Princeton - While there is no doubt that the Tigers are the prohibitive Ivy favorite (barring further backcourt injuries), Princeton is shaping up to be the weakest champion since Cornell took home its second of three-straight titles in 2009.

Much like Zack Rosen, Ian Hummer used one out of every four offensive possessions for Princeton last year (again, that's total, not just during the time he was on the floor). With Douglas Davis bombing with precision early and often from outside, the Tigers' role players found themselves with tons of space and relatively little urgency to contribute on the offensive end. In fact, no one else on the Princeton team took more than 20 percent of the team's shots when on the floor, as Hummer and Davis were chewing up 57 percent of the attempts when out there together.

That raises some obvious questions. Can T.J. Bray's 40 percent accuracy from deep hold up when instead of taking one in every nine shots for his team, he has to take closer to one in five? Which reserve guard will step up to chew up minutes at the off guard spot, and will he struggle without the safety net of a low usage rate? These questions are relatively minor compared to what all of the other Ivies are currently facing, which is why Princeton is a strong favorite. They're still much stronger questions than an Ivy favorite has faced recently, though, making it likely that this year will be a step back for the league.

Yale - Greg Mangano and Reggie Willhite would have been huge losses for their offensive contributions alone, as they ate up over 40 percent of Yale's possessions at a well above average efficiency rate. The problem is that those two guys were also among the league's Top 10 defensive players, as well.

It will be a different league without the villainous Mangano roaming in the paint, going back-and-forth not only with fellow players, but also opposing fans. For that matter, the Bulldogs will be a different team, too.

Coach James Jones is a cagey veteran, though. With Austin Morgan draining threes, Jeremiah Kreisberg anchoring the paint and point guard Michael Grace making plays (when he holds onto the ball), Yale still has a solid core with All-Ivy talent. As usual, Jones has done a great job of stockpiling productive Ivy players who flew a bit under the radar and now can unleash guys like Jesse Pritchard, Brandon Sherrod and Justin Sears to fill the gaping holes left by Mangano and Willhite.

In a weaker edition of the league, Jones might still be a lock to guide his squad back to the upper division, as he has done every year since 2000. In the "new Ivy League," however, it takes two dynamic two-way players just to finish fourth. It's hard to see him hitting that mark again with significantly less talent this year.

This is an always interesting read and I think I speak for many Ivy fans when I thank you for providing it. I wonder if you would consider running your model again on the eve of conference play in January. There's a lot of new information to be gained before then, especially this year with all the talent losses around the league.

ReplyDeleteIn 2010-11, for example, your model liked Princeton and Harvard but, by the time conference play began, the Crimson seemed like a clear favorite, making the Tigers' eventual NCAA bid seem a bit more like overachieving, even though P and H seemed even at season's start.

Absolutely. I'll try to post that information here, but if I don't, it will be on the Basketball-U Ivy Message Boards, for certain.

ReplyDeleteI continually re-run the model after each game, gradually phasing out the preseason projections in favor of regular season actuals. But I'll probably highlight where things stand on the eve of league play in a separate piece.

The ebb and flow of the rankings and projections is fun to keep an eye on as the season progresses.

This is really helpful. I have read this and achieved a lot of information.

ReplyDeleteUsed Roller

I find it more than a little ironic that your dismissiveness of Nate Silver's 538 forecast is very comparable to the objection of the Cornell Basketball Blog to your fine analysis of Ivy basketball. I would summarize both of your criticisms as, "Don't bother me with all of that math and statistics mumbo jumbo. Your conclusions just don't *feel* right. The race is a lot closer than you think it is."

ReplyDeleteIt seems that many observers are more comfortable with the approach of data-driven analysis when they like the output. Fortunately, there will soon be an empiricial confirmation or refutation of both of your models. I, for one, expect both you and Nate Silver to be proven correct.

Thanks for bringing this up, because it's a question I get a lot.

ReplyDeleteI am not at all dismissive of Nate's 538 forecast. He has a model which has been built to fit historical data and to use that to project the future, just like mine. And as I'm sure he does with his, I constantly re-evaluate the assumptions underlying my model. For instance, this offseason, I did a ton of work on home court advantage to replace a previous assumption that all HCA is created equal (it isn't). I've also done some tweaking to the pace at which my preseason projections are filtered out of model and the way I use similarity scores to project player performance for preseason rankings.

Models undergo a constant evolution, in which prior assumptions are tested and shred and new data restructures the weighting of the inputs.

My points about Nate's model are not meant to say that data-driven analysis of political outcomes is wrong as a concept. I'm merely hypothesizing about assumptions backing the model - primarily that if there is a difference between a build-up from state models and national models, the difference might arise from different composite turnout models. Nate's a pro and has way more data than I do, so it's entirely possible that his assumption will be right. But even in the unlikely event that my assumption is right, that a) would have to be pretty severe to change the result and b) wouldn't be an argument against using data-driven analysis to predict the outcome, just an argument to tweak the assumptions.

Hopefully, that makes sense.

(Also, as a further note, I'm pretty ardently against both parties for a variety of reasons, so there isn't really an outcome Tuesday for me to like. I'm just fascinated by the numbers and the predictive process - the outcome is only really interesting to me in so much as it's another data point.)

In your proposal to scrap AI averages for each Ivy in favor of higher AI floors, are you suggesting that the differential between various Ivies be maintained, in particular that Yale, Princeton and Harvard be held to a higher AI threshold?

ReplyDeleteParenthetically, I'm sure you've noticed that Nate Silver's 538 forecast was 100% vindicated on Election Day. The electoral race was not at all close and Silver called the component state races perfectly. His underlying assumptions on the turnout demographics must be right on target.

The proposal to scrap AI averaging would involve an AI floor of 180 for all schools. There would be no differences in what one school could accept versus another. (Now, schools would obviously have their own internal standards of their choosing, so this wouldn't mean that every 180+ would automatically get accepted, but at least that decision would be completely up to the school in question).

ReplyDeleteAs for Nate Silver, from a forecast perspective, he was very close to 100% right (great HSAC post on this... http://harvardsportsanalysis.wordpress.com/2012/11/08/nate-silver-and-forecasting-as-an-imperfect-science/), but more importantly, the mechanism for building the model revealed (amazingly, in my view) that it is the national polls which were quite biased. Building up from the state polls, something which I felt would increase the noisiness of the projections, was actually the way to get to a more accurate number. Very interesting stuff.